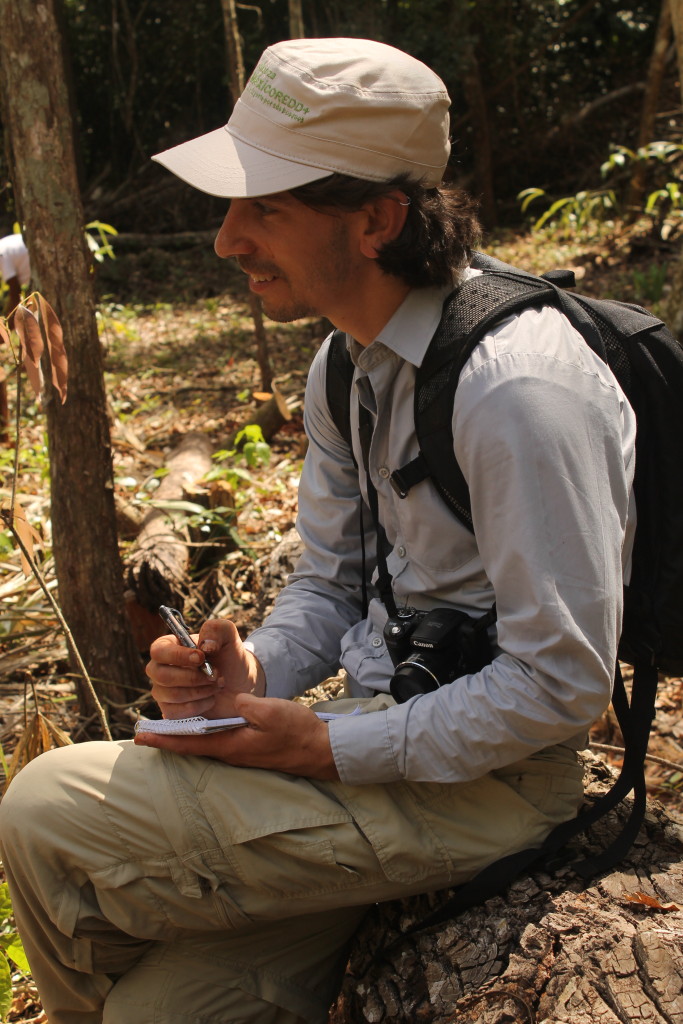

Photo by Phillip Sauerbeck

A version of this post was published February 20, 2014 on The Sieve.

I suspect no other relationship is more complex and fraught than that between humans and trees. I’ve been wanting for a long time to write something about it, but every time I try, I get overwhelmed. Where to begin?

For us humans, it indeed goes back to the beginning: Adam and Eve learned of their own humanity from a tree. Or if you prefer more scientific stories, our ancestors took a crucial step in speciating from other apes by descending from the trees. Since then we haven’t gone far from the tree, so to speak. We have eaten from trees, climbed trees, lived in trees, worshiped trees, studied trees, planted trees, hugged trees, and saved trees. We have also, at various times, cut trees down for fuel, for lumber, to make paper, to make weapons, to clear farmland, to create subdivisions, because they threatened our infrastructure, because we didn’t like where they were growing, and for no reason whatsoever.

After hundreds of thousands of years of shared history, have we and trees come to understand each other better? Three stories I have come across recently suggest the answer is, it’s still complicated.

A local tale

The first story is from my own neighborhood of Mount Rainier, a small city just northeast of Washington, DC in the watershed of a minor river called the Anacostia. The Anacostia River, which flows into the better-known Potomac, was once a commercially significant waterway. But as generations of people felled surrounding trees, bare soil eroded, silting up the water and reducing the clear-flowing river to a shallow muddy creek. One of the many things trees do for us—one of their ecosystem services, to use the fashionable term—is hold our land in place.

The Anacostia may be a trickle of its past self, but it can still flood. And as people have understood for a long time, when you deforest a watershed, rain washes more quickly into waterways, and flooding gets worse. Cities along the river responded to the elevated flood risk by building a levee.

Now, ostensibly to protect the levee, several hundred trees near a channelized tributary of the Anacostia going through Mount Rainier are about to be cut down. The byzantine reasoning is as follows: After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the Army Corps of Engineers strengthened its requirements for levee certification, which is supposed to guarantee that a levee will stand up to a 100-year flood. People who want to insure property behind a levee have to buy flood insurance unless their levee is certified, so the Army Corps’ rules affect a lot of people. The new rules, in addition to raising the minimum levee height, require that trees growing within 15 feet of a levee be removed, because the Corps believes tree roots could compromise the levee’s integrity. This means that more than 200 trees in Mount Rainier, from small, scraggly things no one is likely to miss to 100-or-more-year-old sweetgums and tulip poplars, are destined for the chainsaw.

A view from the levee. The trees on the far side of the concrete wall are on the chopping block.

(Quick pause for disclosure: I am on Mount Rainier’s Tree Commission, which is advising the city on the levee issue. But all opinions expressed here are mine, and all the facts I’m reporting were presented at a public city council meeting. For a further perspective on the urban forest, check out council member Jesse Christopherson’s blog post.)

In the grand scheme, the number of sizable trees we stand to lose is small. And the county has agreed to give the city two new trees for every one that is cut down, so Mount Rainier could emerge in a few decades with more tree cover than it had before. But I’m struck by the perverse logic of the situation: People cause a problem (increased flooding) by cutting down trees and building in floodplains, and then pursue a technological solution that leads to cutting down more trees.

And for what? The new levee may protect against the current 100-year flood, but what about the 100-year flood 50 years from now, when climate change has loaded the dice in favor of stronger storms? We can’t keep building levees higher forever. A better strategy would be to reduce the peak flows that levees have to deal with, which would mean increasing tree cover and, perhaps, giving the river back some of its historic floodplain.

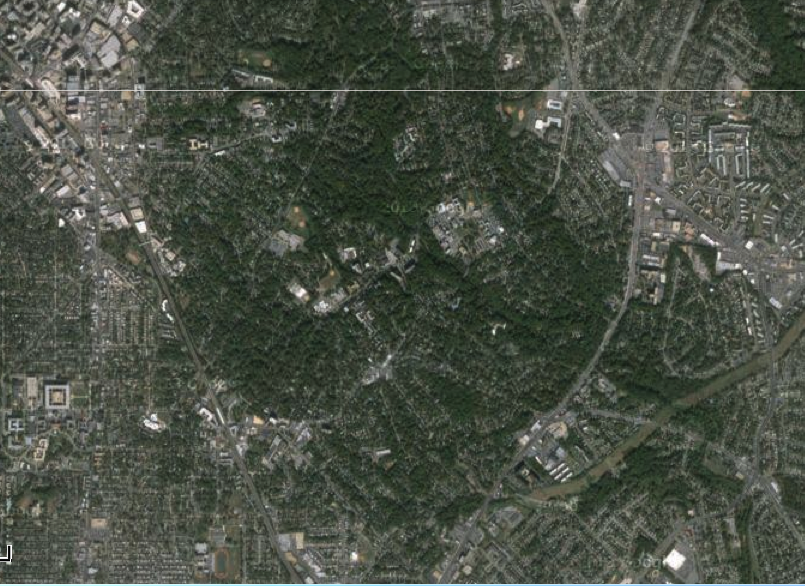

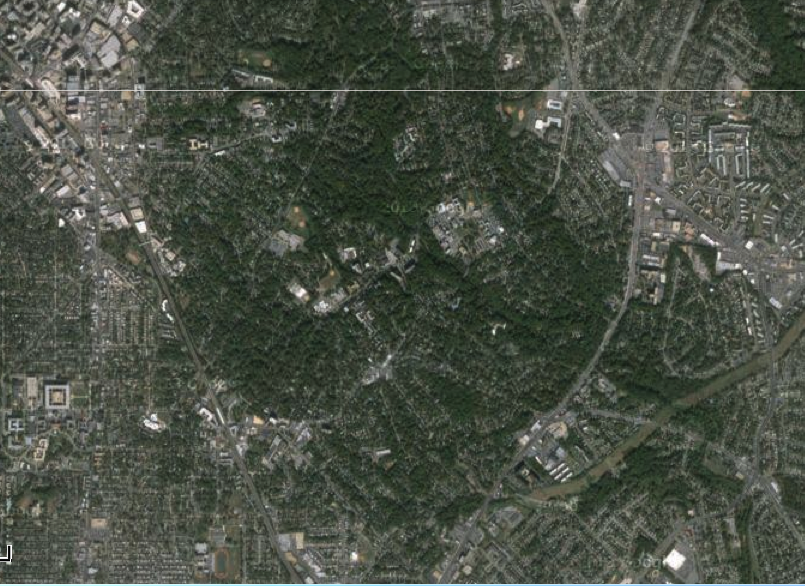

It’s unrealistic to hope tree cover will make a full comeback in an area as densely settled as the DC suburbs. But there’s plenty of room for improvement over the current 25 percent, the number reported by the Anacostia Watershed Society. The nearby city of Takoma Park, which has long protected its trees, stands out in satellite images for its dense foliage compared to neighboring areas. Other municipalities, including Mount Rainier, are now taking steps in that direction with laws that protect large trees on public and private land. Trees are our allies, and the loss of a healthy tree anywhere in the watershed makes all of us more vulnerable.

Tree-friendly Takoma Park, MD from the sky. From google maps.

The global view

Flooding is a local problem, and the number of trees in the Anacostia watershed will probably always be of concern mostly to the people living in the watershed. But in another important sense, we are all united in our dependence on every tree everywhere. That is because trees store carbon in their tissues. This fact that was perhaps almost incidental until people began putting way too much fossilized carbon into the atmosphere; now, our collective future could depend on it. The world’s forests have become crucial reservoirs of carbon and sponges for some—though far from all—the carbon spewing from our cars and factories.

A new map made by a team of researchers at the University of Maryland gives us a global view of how well this global carbon sponge is working. Unfortunately, the picture, which combines over 650,000 satellite images, is troubling. Major areas of tree loss show up angry red both in tropical South America and the boreal forests of Alaska, Canada, and Russia. Things are more mixed in the U.S. South and Indonesia, and a few pockets of tree gain are sprinkled here and there. But the big picture, which the authors reported in Science, is that the world lost around 1.5 million square kilometers of forest between 2000 and 2012. As Peter Ellis, a forest carbon scientist at the Nature Conservancy (and incidentally a Mount Rainier neighbor) observes on his blog, “we are losing forests a lot faster than they can grow themselves.”

Credit: NASA Goddard, based on data from Hansen et al., 2013.

But there are reasons for hope. Forests in much of the U.S. have staged a major comeback in the past century, and are making small but significant dents in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. And a recent study published in Nature showed that even old trees keep growing, soaking up more and more carbon the larger they get. Forests can buy us some time to deal with climate change before the worst impacts hit—but only if we leave trees standing.

The specter haunting this whole discussion is the possibility that if temperatures get warm enough, forests could start to release more carbon than they pack away. This could happen through increased respiration (in addition to consuming carbon, trees breathe out carbon dioxide just like we do) as well as increases in decomposition rates and forest fires. Forests as carbon sources would be an unmitigated global disaster, dramatically amplifying global warming and potentially making parts of the world simply hellish. Should this happen, the authors of another recent Nature article recommend that we harvest our forests and turn them into buildings and other structures that won’t decay and release their carbon. If we get to the point where we are cutting forests to save the climate, I don’t think I want to be around for it.

I find it wonderful that trees, which I love anyway, also store carbon, and have the potential to blunt the full impacts of our carbon pollution (though this borrowed time is worth nothing if we don’t use it to reduce that pollution as fast as possible). But I worry about the implications of viewing trees as big sticks of solid carbon—what one might call the widgetization of nature. The Nature authors manage to write a whole article about trees without mentioning a single actual species. That kind of abstract view makes it easy to imagine harvesting those trees if they become carbon sources, regardless of the other benefits they may confer to people or other living things. It’s a view that may see the forest, but misses the trees.

Losing a loved one

As anyone who has been to a forest knows, there is no such thing as a generic tree. There are only white oaks, sugar maples, pitch pines, and so on. And each tree is the basis of a unique food web, many of which contain organisms not yet known to science. Trees of different species are not interchangeable with each other, nor with other things we might discover that do an equally good job of holding carbon. We have only barely begun to learn how the system works. To paraphrase Aldo Leopold, this is not the time to be throwing pieces of the machine away because we think we don’t need them.

This brings me to my third story, in which a particular tree native to my part of the world is disappearing, not because anyone wants it to, but nevertheless for an entirely human-caused reason. As my friends and family know, I have become fairly obsessed with this tree, the eastern hemlock, or Tsuga canadensis. I point it out on hikes and turn branches over to look for the fluffy white egg sacs of the hemlock woolly adelgid. I have written about this invasive insect, which is destroying nearly all the hemlocks in the eastern U.S. The adelgid was apparently introduced to the U.S. in or around 1951, by accident, on a shipment of Japanese hemlocks to a Richmond, VA nursery (the insect is native to Asia and hemlock species there tolerate it just fine). That such a catastrophe could originate from so trivial an incident is part of what makes the whole thing so spooky.

Hemlocks lining a stream in western Maryland

Hemlock bark was once used to tan leather, but otherwise the tree has never been of much value economically. The wood splinters easily, and except up north, the tree lives mostly in river valleys where few people go. In terms of ecosystem services, the trees’ perpetual shade keeps trout streams cool, and its evergreen canopy captures rain and snow all year round. These are not trivial benefits, but they are not the kinds of impacts likely to inspire a national conservation movement. So it is hard to imagine cash-strapped governments spending a bunch of money to save a tree whose loss will cost few, if any, jobs. Indeed, as Richard Preston reported in 2007 in the New Yorker, governments pretty much haven’t.

But viewed another way, the costs if the hemlock disappears will be immense—literally incalculable. For what is the value of a species? A species lost is lost forever, so one could argue its value is infinite.

To be clear, the eastern hemlock itself is unlikely to go extinct, at least in the near future. Insecticides can protect individual trees if applied regularly, and winters in the upper Midwest and Canada, where many hemlocks live, are too cold for the adelgid to survive (though global warming could eventually remove that protection). But far more than the tree is at stake. Entomologist Louise Rieske-Kinney and her students at the University of Kentucky have studied the organisms living in hemlock-shaded valleys. The scientists have found that certain aquatic flies eat hemlock needles that fall into the streams. Certain spiders eat those flies, and fish eat those spiders. Removing the hemlock is like pulling the bottom block from a toy tower—the rest of the blocks come crashing down too.

Changes in streams may just be the beginning. Preston described in his article climbing (now-dead) hemlocks in North Carolina and seeing a whole world living just in the trees’ canopies. “There were small hummocks of aerial moss, spiderwebs, insects associated with hemlock habitat,” he wrote in 2007. “There were mites living in patches of moss and soil on the tree, many of which probably had never been classified by biologists. The hemlock forest consists in large part of an aerial region that remains a mystery, even as it is being swept into oblivion.”

-

A hemlock graveyard in Shenandoah National Park

Since 2007, scientists have shed some light on this mystery. Talbot Trotter, an ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service in Connecticut, told me he and his students have discovered hundreds of insects, mites, and spiders that seem to live on hemlock branches and nowhere else. The researchers would know more, except there is hardly anyone in the world with the expertise needed to classify the species they are finding.

Meanwhile, forest managers up and down the Appalachians lead small armies of insecticide sprayers into the woods. Their goal is to hold off the adelgid, at least from the largest and most visible trees, while biocontrol researchers try to breed and release an effective adelgid predator. But it is an uphill battle; predatory beetles that have been released often consume all the adelgids in a small area and then disappear. No one to my knowledge has gotten a permanent population established.

The extraordinary effort and care of these scientists and forest managers is the flip-side of the carelessness with which the adelgid was released onto this continent. Hundreds of people are now dedicating careers to understanding the insect and the hemlock, and to slowing—and perhaps eventually reversing—the damage. They’re not doing this because it pays well or because it’s glamorous work, or even because we as a society need the eastern hemlock. They’re doing it because they love this tree.

- What mysterious forms live in the canopy?

A tale of survival

It’s not just the hemlocks that need love. The emerald ash borer is destroying the nation’s ashes. Asian longhorned beetles are attacking the great maple forests of the north. A fungal disease spread by a scale insect threatens the beech (another one of my favorites). The mountain pine beetle has brought down millions of pine trees out west and could do even more damage if it makes its way east. Already the American chestnut and American elm have largely succumbed to their own introduced pathogens. Invasive species amped up on climate change are doing what humans with their saws and axes could not—excising whole tree species from the landscape.

And yet, I suspect most trees will come through even this latest round of insults, as they have countless times before. The eastern hemlock was once far more abundant, but pollen studies show that it declined dramatically somewhere between five and six thousand years ago. No one quite knows why, but climate change and disease have been suggested. Still, the eastern hemlock is far from rare, and even in places where the adelgid has ravaged the older trees, new green shoots push their way up. Perhaps thousands of years from now, hemlocks will once again find conditions favorable and spread out over the land.

It is tempting to see trees as passive players in this drama, merely reacting to climate shifts, disease, and now humans and their invasives. But I have come to think of trees as playing the long game. They spread themselves far and wide, bank their seeds for decades or longer, and reproduce both sexually and asexually. For all the clear-cutting and species shlepping we have done on this continent, we have only driven two of its native tree species extinct in the wild, according to USDA plant geneticist Richard Olsen. (And at least one of these, Franklinia alatamaha, is still in wide cultivation). In short, trees know how to survive.

Yes, it’s not the trees I worry about. It’s the overconfident, impulsive, short-lived primates.

Writer’s note: this post was amended to reflect the fact that the Anacostia levee was not built in response to 1972’s Hurricane Agnes (it was actually constructed in the 1950s).

While these statistics are sobering, I realize their relevance to me is unclear. For one thing, they may not reflect the recent upsurge in biking, which has started to make the activity safer in some places (more on this later). But more to the point, they don’t answer the question I really need answered, which is what is my personal level of risk, at my level of biking competence, when I ride along my typical routes?

While these statistics are sobering, I realize their relevance to me is unclear. For one thing, they may not reflect the recent upsurge in biking, which has started to make the activity safer in some places (more on this later). But more to the point, they don’t answer the question I really need answered, which is what is my personal level of risk, at my level of biking competence, when I ride along my typical routes?